- Visibility 720 Views

- Downloads 77 Downloads

- Permissions

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.034

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Abstract

Drug delivery to certain eye tissues has long been a major challenge for ocular scientists. Some problems with the standard formulations of drug solutions given as topical drops led to the introduction of various carrier systems for ocular dispersion. A lot of work is being done on ocular research to create safe, novel, and patient-friendly methods of pharmaceutical administration. After being enclosed in nanoscale carrier systems or devices, drug molecules are administered using invasive, non-invasive, or minimally invasive techniques. In the years to come, drug delivery may be greatly enhanced by the creation of non-invasive sustained drug delivery devices and studies into the viability of topical application to deliver medications to the posterior region. The difficulties related to a number of anterior and posterior segment diseases may be significantly reduced by recent advancements in the administration of ocular medications.

Introduction

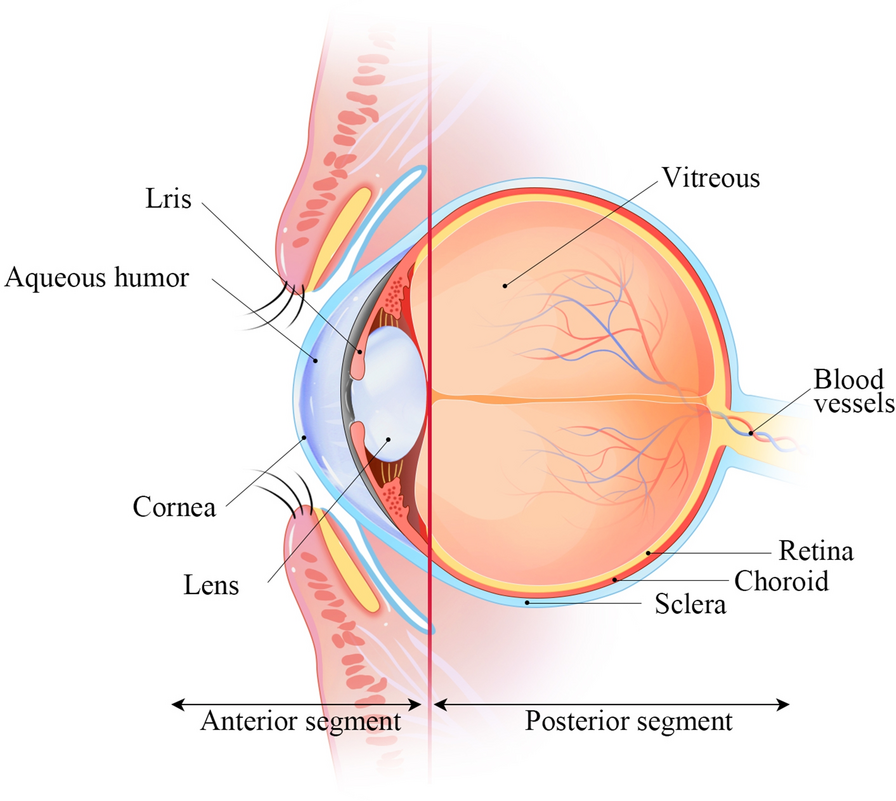

The distinctive design and physiology of the eyes present substantial hurdles for pharmacologists and drug delivery professionals. One major challenge is developing a medication delivery system that specifically targets specific eye tissues. The anterior and posterior regions of the eye can be distinguished by structural changes after drug administration ([Figure 1]). Dynamic barriers include blood flow, tear dilution, and lymphatic clearance, while static barriers include sclera, corneal, and retinal layers.[1], [2] Eflux pumps also make it difficult to transport medication alone or in dosage form, especially to the posterior portion. Many eye disorders, such as cataracts, glaucoma, anterior uveitis, and allergic conjunctivitis, affect both anterior and posterior areas. Recent research has focused on identifying influx transporters and developing transporter-targeted parent drug delivery. Innovative pharmaceutical delivery innovations, such as bioadhesive gels and fibrin sealant-based approaches, are being developed to maintain medication levels in the target area.

Discussion

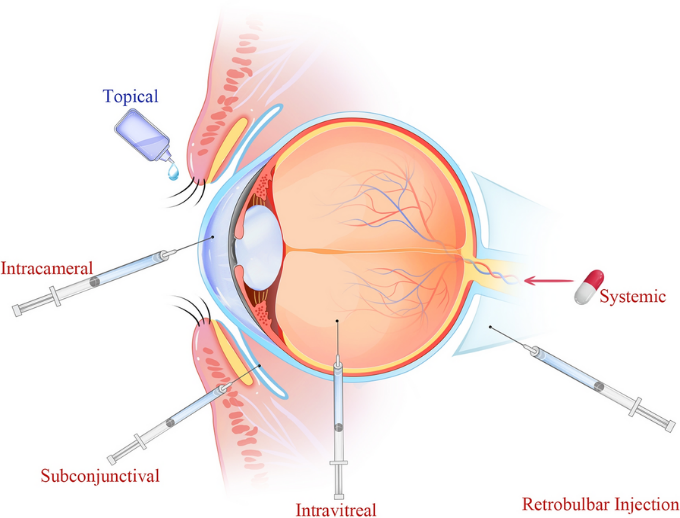

Direct implementation is the most popular non-invasive medication administration method for conditions affecting the anterior region, making up almost 90% of marketed ophthalmic formulations. However, external solutions have negligible ocular retention due to physiological and anatomical constraints such as static and dynamic barriers, reflex blinking, naso-lachrymal drainage, and tear turnover. [3], [4], [5] Consequently, fewer than 5% of locally administered drugs can be administered to the posterior segment ocular tissues using various delivery techniques, including intravitreal injections, periocular injections, and systemic administration. Intravitreal injection is the most widely used technique for treating posterior ocular diseases, but it can cause negative outcomes like endophthalmitis, haemorrhage, retinal detachment, and poor patient tolerance.[6] The ocular static and dynamic barriers mentioned above hinder medication penetration even though transscleral distribution is comparatively easy, less invasive, and patient-friendly ([Figure 2]). Transscleral drug delivery with periocular administration is another technique for administering medications to the posterior eye tissues. Permeation enhancers, such as ion-pair forming agents, prodrugs, cyclodextrins, and iontophoresis, are used to enhance ocular penetration.[7], [8], [9] However, some studies have found that permeation enhancers can result in local toxicity.[10] Hydrophobic drug molecules are transported across aqueous solutions by cyclodextrins, making it easier to distribute drugs to the surface of biological membranes.

There are numerous approaches to ocular medication administration now in use. The most popular approach is direct administration of medication. The recommended treatment for eye conditions such infection, inflammation, DED, glaucoma, and allergies is topical ophthalmic treatments. They make up 95% of the products that are sold commercially worldwide. However, the anatomy of the eye restricts the transport and absorption of drugs, necessitating large doses and frequent injections. Increasing pre-corneal retention time and improving medication permeability are two methods to increase bioavailability. Among the techniques are prodrugs, collagen corneal shields, enhancing factors, mucus osmotic fragments, and medical contact lenses.

The blood-aqueous barrier and the blood-retinal barrier are the main obstacles to the transmission of ocular medications in the anterior and posterior segments following systemic injection, respectively. The iris/ciliary blood vessel endothelium and the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium are two distinct cell layers that make up the blood-aqueous barrier, which is situated in the anterior region of the eye. Tight junctional complexes in both cell layers block solutes from entering the intraocular space, including the aqueous humor.[11] Therapeutic medications cannot enter the posterior region of the blood due to the blood-retinal barrier. The two cell types that make up the inner and outer blood-retinal barriers are retinal capillary endothelial cells and retinal pigment epithelium cells. A single layer made up of incredibly specialized cells known as retinal pigment epithelial cells sits between the choroid and the neural retina. Retinal pigment epithelium facilitates biochemical processes by allowing molecules to pass selectively between choriocapillaris and photoreceptors. It also protects the visual system by absorbing and converting retinoids.[12] Due to its wider vasculature than retinal capillaries, drugs can quickly reach the choroid following oral or intravenous dosing. Drug molecules in the circulation readily adapt to the extravascular space of the choroid due to the fenestrated choriocapillaris. Nevertheless, additional drug penetration from the choroid into the retina is inhibited by the outer blood-retinal barrier. The blood-retinal barrier, which tightly controls drug penetration from blood to the retina, makes systemic administration of the medication to the retina difficult even if it is the best strategy.

Another method of administration is oral delivery. There are several reasons why oral delivery[13] or topical delivery in combination[14] has been studied. Therapeutic concentrations in the posterior region could not be attained with topical treatment alone. Additionally, oral delivery was examined as a possible non-invasive and patient-favored therapy option for chronic retinal problems in comparison to injection treatment. However, the effectiveness of oral delivery is limited by the inaccessibility of many of the targeted ocular tissues, requiring substantial dosages to provide meaningful therapeutic benefits. Systemic adverse effects could result from this.

For example, oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, such as acetazolamide and ethoxzolamide, have been discontinued in most glaucoma therapy cases due to their systemic toxicity.[15] Only a small number of compounds have been studied for the administration of drugs through the eyes, and the oral route is not very common. These include analgesics, antibiotics, antivirals, omega-6 fatty acids, and antitumor drugs, among other pharmacological categories. The drug's high oral bioavailability is a crucial prerequisite for the oral route in ocular applications. After being consumed, substances in the bloodstream also need to cross the blood-aqueous and blood-retinal membranes.

Intravitreal and periocular delivery are possible additional methods. Although these routes are not particularly patient-compliant, they are utilized in part to overcome the inefficiency of topical and systemic dosage in delivering therapeutic drug concentrations to the posterior portion. Furthermore, because of the potential for adverse consequences, elderly people are less likely to favor systemic administration as a delivery technique. Compared to the intravitreal method, the periocular approach—which includes subconjunctival, subtenon, retrobulbar, and peribulbar administration—is relatively less invasive. The transscleral pathway, the anterior pathway via the tear film, cornea, aqueous humor, and vitreous humor, and the systemic circulation through the choroid are the three ways that the medication delivered by periocular injections can reach the posterior segment.[16]

The conjunctival epithelial barrier, which limits the pace at which water-soluble medications can penetrate, is avoided via subconjunctival injection. The cornea-conjunctiva barrier is thus circumvented via the transscleral pathway. Drug entry to the posterior region is, however, restricted by a number of dynamic, static, and metabolic barriers. Conjunctival and lymphatic circulation are examples of dynamic barriers. Conjunctival and lymphatic circulation are examples of dynamic barriers. Some writers reported quick drug clearance after subconjunctival injection using these methods.[17] As a result, its ocular bioavailability is reduced as the formulation is able to penetrate the systemic circulation. Drug clearance from the subconjunctival region is therefore one of the primary variables regulating the vitreous drug levels following subconjunctival administration. Since the cornea is less permeable than the sclera, it is unable to provide a robust barrier.

Furthermore, the molecular radius primarily determines permeability across the sclera, with lipophilicity having no effect, in contrast to the corneal and conjunctival layers.[18] The choroid is an important barrier because of the strong choroidal blood flow, which may cause a significant amount of the drug to be removed before it reaches the neural retina. Additionally, blood-retinal barriers limit the medications that can reach the photoreceptor cells.

Because the molecules are injected directly into the vitreous, intravitreal injections have clear advantages versus periocular injections. Nevertheless, the drugs are not dispersed equally throughout the vitreous. Larger molecules have limited diffusion in the vitreous, whereas small molecules can move quickly through it. The distribution of the medicine is also influenced by its molecular weight and pathophysiological state.[19] Furthermore, the vitreous acts as a barrier to prevent the transmission of retinal genes following an intravitreal injection. A negatively charged glycosaminoglycan that is present in the vitreous, hyaluronan can interact with lipid DNA complexes that are cationic, polymeric, and liposomal.[20] This interaction may lead to considerable immobilization and aggregation of DNA/cationic liposome complexes.[21] Similarly, the shape and surface charge of nanoparticles determine their mobility in the vitreous. Because polystyrene nanospheres stick to collagen fibrillar structures, they are unable to diffuse easily into the vitreous.[22] Thus, the surface of nanospheres has been altered using hydrophilic PEG chains. Anionic nanoparticles with a zeta potential of -33.3 mV diffused more easily in the vitreous than cationic particles with a zeta potential of 11.7 mV, according to a recent study employing human serum albumin nanoparticles.

Another method that is currently being used is melanin binding. Drug disposal in the eyes may be altered by melanin. The quantity of free medication accessible at the designated site may alter as a result of interaction with this pigment. Therefore, melanin binding may significantly decrease the effectiveness of pharmaceuticals.[23] Melanin is found in the eye's uvea and retinal pigment epithelium. Through simple charge transfer, Van der Waals forces, and electrostatics, it binds to medications and free radicals. [24]

All basic and lipophilic medications bind melanin, according to the information now available.[25] Although it does not necessarily indicate ocular toxicity, drug binding to melanin has important pharmacological implications and should be carefully examined before delivering drugs to the eyes. Medication concentrations and response in anterior ocular tissues are impacted by melanin binding in the iris-ciliary body.[26] Larger dosages are required since a medication that is melanin-bound is typically not available for receptor binding.[27] After a transscleral or systemic drug injection, the amount of drug uptake into the retina and vitreous is also influenced by the melanin in choroid and RPE. Compared to more hydrophilic beta-blockers, lipophilic beta-blockers exhibit a substantially longer penetration lag-time via bovine choroid-RPE due to melanin binding.[28] Melanin has also been shown to improve the binding of lipophilic substances to the bovine choroid-Bruch membrane. Because the sclera lacks melanin, the choroid-Bruch membrane is more resistant to solute penetration. [29]

Systems of Ocular Medication Delivery Based on Nanotechnology

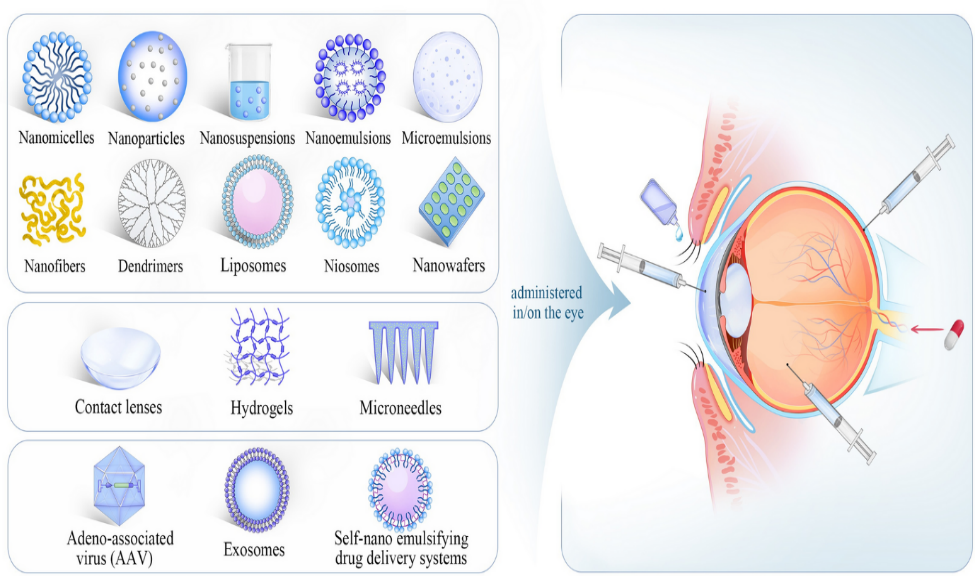

To overcome ocular drug delivery obstacles and increase drug bioavailability, several drug delivery systems have been created. Developing nanocarriers has several advantages, including overcoming ocular barriers, increasing trans corneal permeability, extending drug residence time, decreasing dosing frequency, improving patient compliance, lowering drug degradation, achieving sustained/controlled release, drug targeting, and gene delivery. [30] Numerous ocular drug delivery systems, such as nanomicelles, nanoparticles, nanosuspensions, nanoemulsions, nanofibers, dendrimers, liposomes, niosomes, nanowafers, microneedless, and exosomes, ([Figure 3]) have shown impressive delivery capability in both in vitro and in vivo studies. These systems prolong the duration of a drug's residency in the eye and increase its permeability across ocular barriers. [30], [31]

Nanomicelles

It is a type of colloidal drug delivery system, can contain therapeutic compounds at their core and then self-assemble in a solution. They are produced quickly when the concentration of the polymer reaches a threshold known as the critical micellar concentration. They are made of block copolymers or amphiphilic surfactants. Hydrophobic pharmaceuticals can be encapsulated in the hydrophobic core of nanomicelles thanks to hydrophobic interactions. This colloidal dosage form can be used to create clear aqueous solutions that are appropriate for topical use as eye drops. They fall into two general categories: polymeric and surfactant nanomicelles. The US FDA has approved Cequa, a nanomicellar formulation of 0.09% cyclosporine-A, for the treatment of dry eye condition. It showed greater tear production and a quicker onset of action. [32] In vivo studies showed better absorption in the anterior ocular tissues in comparison to cyclosporine-A emulsion. Polymeric nanomicelles derived from block copolymers can be conjugated to form diblock, triblock, or pentablock copolymers.[33] By solubilizing hydrophobic drugs, they can improve their delivery to the tissues of the eyes. The nanomicellar delivery of nucleic acids, such as oligonucleotides, plasmid DNA, microRNA, and siRNA, is a recently developed field of research.

Nanoparticles

They are minuscule, non-biodegradable particles, can be used to transport medications to the tissues of the eyes. They range in size from 50 to 500 nm and can pass through ocular barriers to administer medications over an extended period of time. They are composed of biodegradable substances such phospholipids, metals, lipids, and polymers. These nanoparticles are used to provide drugs to the tissues of the eyes. They include natural polymers, polylactides, polycyanoacrylate, and poly (D, L-lactides). Nanospheres and nanocapsules are the two types of nanoparticles. Because of their mucoadhesive properties, which improve absorption and reduce dosing frequency, nanocapsules have more benefits. The ability of nanoparticles to enter the eyes is greatly influenced by their surface charge; cationic nanoparticles stay on the surface of the eye longer than anionic nanoparticles.[34] Additionally, colloidal nanoparticles can increase trans-corneal permeability and increase the solubility of highly hydrophobic drugs. Moreover, drugs with low water solubility are converted into nanosuspensions, which produce high-energy crystals that are insoluble in organic or hydrophilic media. Solutions of polymeric nanoparticles prepared with inert polymeric resins can improve drug release and bioavailability. These carriers are ideal for ophthalmic drugs since they do not cause irritation to the cornea, iris, or conjunctiva.

Niosomes

For hydrophilic and hydrophobic medications, niosomes are bi-layered, chemically stable nanocarriers. They are biocompatible, biodegradable, and nonimmunogenic, which enhances drug contact time and absorption. For the delivery of eye medications, a modified form known as discosomes, which have a diameter of 12 to 16 𝜇m, can also be employed. They are distinct from niosomes, which consist of SolulanC and nonionic surfactants. Using niosomal carriers, genciclovir, cyclo-pentolate, and timolol have been administered. [35]

Nanoemulsions

Materials having diameters ranging from 20 to 500 nm that are translucent, kinetically stable, and thermodynamically unstable are called nanoemulsions. As non-invasive, reasonably priced medication delivery methods, they are frequently used to treat eye conditions as glaucoma, fungal keratitis, herpes simplex keratitis infection, and diabetic retinopathy (DED). Among its benefits are increased ocular bioavailability, extended drug release, robust penetration, extended anterior corneal retention time, and simple sterilization enhancement. Using chitosan and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, Jurišić Dukovski et al.[36] created a functional cationic ophthalmic nanoemulsion that maintained the tear film and prolonged the period of drug retention. A ciprofloxacin-loaded nanoemulsion (CIP-NE) was created by Youssef et al.[37] to improve the effectiveness of treating bacterial keratitis.

Nanofibers

These are fibers having a diameter of 1–10 nm, are produced by electrospinning natural or synthetic polymers. [38] They have a number of advantages, including as a high surface-to-volume ratio, high porosity, adjustable mechanical properties, a strong drug-loading capacity, and the capacity to administer multiple therapeutic agents simultaneously.[39] By enabling drugs to pass through physiological barriers and target tissues, nanofibers can limit drug distribution in other parts of the body and accomplish long-term regulated drug release.[40] They can also be loaded with other drugs, such as gentamicin and dexamethasone to treat bacterial conjunctivitis and pirfenidone and moxifloxacin hydrochloric acid to treat corneal abrasions. Because of their extracellular matrix-like characteristics, nanofibers are easier to use and less expensive than many nanostructured drug delivery technologies. They can be used with other technologies, like hydrogels for intravitreal anti-VEGF drug delivery and a double network patch for corneal wound healing. Because of its high tensile strength, hydrophilicity, strong antioxidant activity, and good transparency, the PUTK/RH patch may be a unique therapeutic option for alkali-burned corneas.[41] All things considered, nanofibers hold potential for application in the delivery of medications, the diagnosis and treatment of diseases, particularly chronic illnesses of the eyes.

Nanowafers

They are tiny, transparent disks that can be applied to the surface of the eye using the tip of the finger, allowing for a prolonged retention time and progressive release of the medicine.[42] Dexamethasone-loaded nanowafers can be used as protective membranes and are an effective treatment for dry eye disease (DED).[42] Axitinib-loaded nanowafers have shown beneficial in treating ocular neovascularization in vivo.[43] PVA nanowafers loaded with PnPP-19 have shown potential in the management of glaucoma.[44] The drugs and polymers found in nanowafers are currently being used in clinical settings and, because of their user-friendliness, may be used in human testing.

Dendrimers

With repeating molecules encircling a central core,[45], [46] dendrimers are nanoscale structures that can conjugate, functionalize, and encapsulate drugs.[47] They are adaptable and can be created into biological macromolecules with several functions for a range of uses.[48] A polyanionic dendrimer with antiviral qualities, astodrimer sodium (SPL7013), has been demonstrated to be effective in treating adenoviral eye infections. It has been demonstrated that systemic hydroxy-terminated poly-amidoamine dendrimer-triamcinolone acetonide conjugates (D-TA), which are essential for the progression of disease, are selectively absorbed by activated microglia/macrophages and retinal pigmented epithelium. The benefits of dendrimers, hydrogels, and nanotechnology are all combined in dendrimer gel particles. Although dendrimers offer useful solutions for issues with solubility, dispersion, and targeting in ocular drug administration, cytotoxicity, inadequate drug loading, disparate formulation techniques, and challenges with large-scale manufacturing are impeding clinical translation. [49]

Contact lenses

These are polymer devices that correct refractive defects and can be made of either hydrophilic or hydrophobic polymers.[50] Gas-permeable contact lenses come in two main varieties: soft and rigid.[51] While improving ocular bioavailability, medicine-loaded contact lenses can reduce the required dosage of a medication. [52] However, there are problems with mechanical properties, water content, transparency, and oxygen permeability.[53] Contact lenses and nanotechnology have revolutionized drug delivery. Immersing contact lenses in drug-containing nanoparticles is the most widely used, simplest, and most cost-effective method of producing them. Contact lenses coated with phomopsidione nanoparticles to cure keratitis[54] and zinc oxide contact lenses with antibacterial properties against ocular pathogens[55] are two examples. Furthermore, for the treatment of glaucoma, contact lenses with integrated microtubes can increase medication absorption and extend drug release duration. [56]

Hydrogels

When administering medications to the eyes, hydrogels—a three-dimensional network of hydrophilic polymer chains with a high water retention capacity—are utilized.[57] By extending the duration of drug retention, maintaining drug release, and co-delivering numerous medications, they can enhance the therapeutic impact of ophthalmic medications.[58] Treatment of eye illnesses has advanced dramatically with the use of hydrogels and nanotechnology. To increase drug retention time and boost bioavailability, different nanoformulations—including nanoparticles, nanomicelles, nanofibers, and nanofibers—have been mixed together.[59] For instance, by combining Soluplus micelles with cyclodextrin solutions, a polypseudorotaxane hydrogel was created to treat anterior uveitis. This resulted in enhanced drug retention, corneal permeability, intraocular bioavailability, and anti-inflammatory effects.[60] Gao et al. created an additional hydrogel, an injectable supramolecular nanofiber hydrogel coated with an antibody, which releases anti-VEGF to prevent retinal vascular proliferation, lessen CNV, and lower inflammation. [61]

Microneedle

Low production costs, regulated release, and a minimally invasive method of drug administration are all provided by microneedle technology.[62] It has been thoroughly investigated for the transdermal delivery of a number of therapeutic medications, such as vaccinations, anti-diabetic medications, and anti-obesity medications.[63] Solid, hollow, and dissolving microneedles are among the different types of microneedles that have been studied.[64] When used to treat eye illnesses, these have demonstrated exceptional patient tolerance and effectiveness. For instance, a dissolving microneedle array patch was created to treat the infectious corneal condition known as Fungal Keratitis (FK). In order to prevent the growth of gram-negative bacteria, another study created cryo-microneedles for the ocular administration of live bacteria.[65] A self-plugging microneedle (SPM) was created to simultaneously seal scleral tissues and deliver drugs intraocularly. However, technical factors including bending property, loading capacity, and safety are necessary for evaluating the performance and quality of MN products. [66]

Future Research Roadmap

Extracellular vesicles (Exosomes)

Extracellular vesicles are a type of organelle formed by several cell types. Extracellular vesicles contain a variety of bioactive molecules including as proteins, lipids, RNA, and DNA. They have a nano-size and act as a potent intercellular trigger, causing many physiological and pathological repercussions. In pathological settings, immune cells may make them to limit the progression of inflammation. They play a well-known function in immune-mediated eye disorders, including Sjogren's syndrome and corneal allograft rejection.[67] They may also stimulate the creation of certain matrix components, so encouraging corneal tissue renewal. Additional research is needed to create ocular delivery systems based on exosomes.

Gene therapy

Gene therapy, which uses adeno-associated vectors (AAV) as a drug delivery system, is one option that is being actively researched to address the problem of drug durability. The AAV inserts DNA into patient cells, transforming them into bio factories that code for and make specific proteins such as aflibercept or ranibizumab to treat disorders like age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. This therapy may result in a single treatment for some patients, while others may require additional intravitreal injections on occasion. Gene treatments based on AAVs have showed promise in preclinical and phase 1 and 2 clinical trials, and they are currently being studied in numerous phase 3 trials for a variety of retinal disorders.[68] Intraocular inflammation, as well as iris and retinal pigmentary alterations, can occur after AAV-based gene therapy, although in most cases, topical steroids can be used to manage the inflammation; nonetheless, more severe cases of inflammation and hypotony have been documented.4 Although long-term safety studies are underway, the relative novelty of these therapies prevents us from knowing the full extent of their long-term impacts, particularly 20 or 30 years down the road, and as a result, some caution may be advised. However, the development of more effective viral and nonviral vectors for rapidly and safely transducing ocular cells in the future could address many of these difficulties.

Smart nano-micro platforms

Smart refers to nano-micro matrixes that can significantly vary their mechanical, thermal, and/or optical properties in a controlled or predictable manner, as well as achieve sensing triggering responsibilities through stimuli-responsive features. Unlike conventional nanocarriers, smart nano-micro platforms can reveal precise reactions to exogenous (light, sound, and magnetic fields) or endogenous (pH, reactive oxygen species, and biological molecules such as DNA and enzymes) factors, allowing them to perform a variety of functions, including site-specific drug delivery, bio-imaging, and bio-molecule detection. These intriguing procedures have recently expanded to include ocular delivery. Generally, these revolutionary systems have been employed for cancer detection and management, to increase drug/agent bioavailability, reduce side effects, and improve safety and efficacy. [69], [70]

Tissue engineering

Tissue engineering investigations are categorized into two categories. The first form is additive tissue engineering, which replaces cells or tissue or attempts to allow the growth of something that no longer exists. The second form is arrestive tissue engineering, which eliminates uneven growth. Nanosystems can be used to generate both additive and arrestive tissues. Nanosystems-based tissue engineering applications include retinal ganglion cell viability testing,[71] retinal ganglion cell healing, [72] nanofiber scaffold construction,[73] corneal endothelial cell transplantation,[74] and retinal cell apoptosis inhibition,[75] Scientists have begun to investigate if nanotools and nanomaterials can be utilized to restore neurological function to the eye's nerve cells.

Conclusion

The treatment of ocular problems is challenging due to the nature of diseases and ocular barriers. Advances in nanotechnology and non-invasive drug delivery techniques are driving the development of novel and inventive ocular medication administration systems. Current ocular drug-delivery systems, such as posterior implants and decreased drug bioavailability, have limitations. Nano formulations like nanomicelles, nanoparticles, liposomes, dendrimers, nanowafers, and micro needles can improve drug bioavailability at anterior tissues like the conjunctiva and cornea. Non-invasive continuous drug administration is crucial for treating skin and eye disorders, as they are more challenging to treat than the latter. Strategies include using liposomes and nanoparticles in droppable gels and coated with bioadhesive polymers. Product formulations that have been modified to improve ocular absorption include viscosity and mucoadhesive polymers.

Modern technologies, such as iontophoresis, liposomes, microspheres, and nanotechnology, have been studied to improve absorption, reduce adverse effects, and provide drugs to the eyes efficiently. Surface-functionalized nanoparticles containing targeting agents such as aptamers, peptides, antibodies, and vitamins have demonstrated greater absorption than nonfunctionalized nanoparticles. Transferrin-conjugated nanoparticles showed 74% more transport across the cornea and conjunctiva in ex vivo cow eyes.

In conclusion, nanoparticles have shown promise in treating glaucoma, dry eye syndrome, and other ocular diseases. However, challenges remain, including the complexity of production technology, the need for improved stability and safety, and the lack of comprehensive in vivo studies. Future research should focus on developing non-invasive ocular drug delivery systems that overcome ocular barriers, extend drug release duration, and maintain therapeutic concentration at lesion sites.

Source of Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Kim S, Lutz R, Wang N, Robinson M. Transport barriers in transscleral drug delivery for retinal diseases. Ophthalmic Res. 2007;39(5):244-54. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, He W, Robinson S, Robinson M, Csaky K, Kim H. Evaluation of clearance mechanisms with transscleral drug delivery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(10):5205-12. [Google Scholar]

- Bourlais C, Acar L, Zia H, Sado P, Needham T, Leverge R. Ophthalmic drug delivery systems--recent advances. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998;17(1):33-58. [Google Scholar]

- Gulsen D, Chauhan A. Ophthalmic drug delivery through contact lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(7):2342-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudana R, Ananthula H, Parenky A, Mitra A. Ocular drug delivery. AAPS J. 2010;12(3):348-60. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudana R, Jwala J, Boddu S, Mitra A. Recent perspectives in ocular drug delivery. Pharm Res. 2009;26(5):1197-216. [Google Scholar]

- Bochot A, Fattal E. Liposomes for intravitreal drug delivery: A state of the art. J Control Release. 2012;161(2):628-34. [Google Scholar]

- Vaka S, Sammeta S, Day L, Murthy S. Transcorneal iontophoresis for delivery of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride. Curr Eye Res. 2008;33(8):661-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gallarate M, Chirio D, Bussano R, Peira E, Battaglia L, Baratta F. Development of O/W nanoemulsions for ophthalmic administration of timolol. Int J Pharm. 2013;440(2):126-34. [Google Scholar]

- Keister J, Cooper E, Missel P, Lang J, Hager D. Limits on optimizing ocular drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 1991;80(1):50-3. [Google Scholar]

- Barar J, Javadzadeh A, Omidi Y. Ocular novel drug delivery: impacts of membranes and barriers. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5(5):567-81. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen L, Ranta V, Moilanen H, Urtti A. Permeability of retinal pigment epithelium: effects of permeant molecular weight and lipophilicity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(2):641-6. [Google Scholar]

- Santulli R, Kinney W, Ghosh S, Decorte B, Liu L, Tuman R. Studies with an orally bioavailable alpha V integrin antagonist in animal models of ocular vasculopathy: retinal neovascularization in mice and retinal vascular permeability in diabetic rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;324(3):894-901. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H, Sakamoto M, Hata Y, Kubota T, Ishibashi T. Aqueous and vitreous penetration of levofloxacin after topical and/or oral administration. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17(3):372-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaki Y. Molecular design for enhancement of ocular penetration. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97(7):2462-96. [Google Scholar]

- Ghate D, Edelhauser H. Ocular drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2006;3(2):275-87. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Csaky K, Wang N, Lutz R. Drug elimination kinetics following subconjunctival injection using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Pharm Res. 2008;25(3):512-20. [Google Scholar]

- Prausnitz M, Noonan J. Permeability of cornea, sclera, and conjunctiva: A literature analysis for drug delivery to the eye. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87(12):1479-88. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A, Anand B, Duvvuri S, JF. The biology of eye. Drug delivery to the eye. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen L, Ruponen M, Nieminen J, Urtti A. Vitreous is a barrier in nonviral gene transfer by cationic lipids and polymers. Pharm Res. 2003;20(4):576-83. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters L, Sanders N, Braeckmans K, Boussery K, Voorde JD, Smedt SD. Vitreous: a barrier to nonviral ocular gene therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(10):3553-61. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Robinson S, Csaky K. Investigating the movement of intravitreal human serum albumin nanoparticles in the vitreous and retina. Pharm Res. 2009;26(2):329-37. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald R, Tandon V, Wurster D, Barfknecht C. Significance of melanin binding and metabolism in the activity of 5-acetoxyacetylimino-4-methyl-delta2-1, 3, 4,-thiadiazolin e-2-sulfonamide. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1998;46(1):39-50. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson B. Interaction between chemicals and melanin. Pigment Cell Res. 1993;6(3):127-33. [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc B, Jezequel S, Davies T, Hanton G, Taradach C. Binding of drugs to eye melanin is not predictive of ocular toxicity. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1998;28(2):124-32. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen L, Ranta V, Moilanen H, Urtti A. Binding of betaxolol, metoprolol and oligonucleotides to synthetic and bovine ocular melanin, and prediction of drug binding to melanin in human choroid-retinal pigment epithelium. Pharm Res. 2007;24(11):2063-70. [Google Scholar]

- Salminen L, Imre G, Huupponen R. The effect of ocular pigmentation on intraocular pressure response to timolol. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl (1985). 1985;173:15-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Wielders L, Schouten J, Winkens B, Biggelaar FD, Veldhuizen C, Findl O. European multicenter trial of the prevention of cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery in nondiabetics: ESCRS PREMED study report 1. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(4):429-39. [Google Scholar]

- Cheruvu N, Kompella U. Bovine and porcine transscleral solute transport: influence of lipophilicity and the Choroid-Bruch's layer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(10):4513-22. [Google Scholar]

- Onugwu A, Nwagwu C, Onugwu O, Echezona A, Agbo C, Ihim S. Nanotechnology based drug delivery systems for the treatment of anterior segment eye diseases. J Control Release. 2023;354:465-88. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasarao D, Lohiya G, Katti D. Fundamentals, challenges, and nanomedicine-based solutions for ocular diseases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2019;11(4). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Mandal A, Gote V, Pal D, Ogundele A, Mitra A. Ocular pharmacokinetics of a topical ophthalmic nanomicellar solution of cyclosporine (Cequa®) for dry eye disease. Pharm Res. 2019;36(2). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- CDT, Torriglia A, Furrer P, Behar-Cohen F, Gurny R, Möller M. Ocular biocompatibility of novel Cyclosporin A formulations based on methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-hexylsubstituted poly(lactide) micelle carriers. Int J Pharm. 2011;416(2):515-24. [Google Scholar]

- Akhter S, Anwar M, Siddiqui M, IA, Ahmad J, Bhatnagar MZ. Improving the topical ocular pharmacokinetics of an immunosuppressant agent with mucoadhesive nanoemulsions: formulation development, in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2016;148:19-29. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Sahoo S, Dilnawaz F, Krishnakumar S. Nanotechnology in ocular drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13(3-4):144-51. [Google Scholar]

- Dukovski B, Juretić M, Bračko D, Randjelović D, Savić S, MM. Functional ibuprofen-loaded cationic nanoemulsion: Development and optimization for dry eye disease treatment. Int J Pharm. 2019;576. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Youssef A, Cai C, Dudhipala N, Majumdar S. Design of Topical Ocular Ciprofloxacin Nanoemulsion for the Management of Bacterial Keratitis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14(3). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Razavi M, Ebrahimnejad P, Fatahi Y, ’emanuele AD, Dinarvand R. Recent developments of nanostructures for the ocular delivery of natural compounds. Front Chem. 2022;10. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Hu X, Liu S, Zhou G, Huang Y, Xie Z, Jing X. Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for drug delivery applications. J Control Release. 2014;185:12-21. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Goyal R, Macri L, Kaplan H, Kohn J. Nanoparticles and nanofibers for topical drug delivery. J Control Release. 2016;240:77-92. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Shi X, Zhou T, Huang S, Yao Y, Xu P, Hu S. An electrospun scaffold functionalized with a ROS-scavenging hydrogel stimulates ocular wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2023;158:266-80. [Google Scholar]

- Coursey T, Henriksson J, Marcano D, Shin C, Isenhart L, Ahmed F. Dexamethasone nanowafer as an effective therapy for dry eye disease. J Control Release. 2015;213:168-74. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Yuan X, Marcano D, Shin C, Hua X, Isenhart L, Pflugfelder S. Ocular drug delivery nanowafer with enhanced therapeutic efficacy. ACS Nano. 2015;9(2):1749-58. [Google Scholar]

- Dourado L, Silva C, Gonçalves R, Inoue T, Lima M, Cunha-Junior A. Improvement of PnPP-19 Peptide Bioavailability for Glaucoma Therapy: Design and Application of Nanowafers Based on PVA. Improvement of PnPP-19 Peptide Bioavailability for Glaucoma Therapy: Design and Application of Nanowafers Based on PVA. . [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi E, Aval S, Akbarzadeh A, Milani M, Nasrabadi H, Joo S. Dendrimers: Synthesis, applications, and properties. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2014;9(1). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Kambhampati S, Kannan R. Dendrimer nanoparticles for ocular drug delivery. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013;29(2):151-65. [Google Scholar]

- Spataro G, Malecaze F, Turrin C, Soler V, Duhayon C, Elena P. Designing dendrimers for ocular drug delivery. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;45(1):326-34. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh A, Kesharwani P, Gajbhiye V. Dendrimer as a momentous tool in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. J Control Release. 2022;346:328-54. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Romanowski E, Yates K, Paull J, Heery G, Shanks R. Topical astodrimer sodium, a non-toxic polyanionic dendrimer, demonstrates antiviral activity in an experimental ocular adenovirus infection model. Molecules. 2021;26(11). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Rykowska I, Nowak I, Nowak R. Soft contact lenses as drug delivery systems: a review. Molecules. 2021;26(18). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Peral A, Martinez-Aguila A, Pastrana C, Huete-Toral F, Carpena-Torres C, Carracedo G. Contact Lenses as Drug Delivery System for Glaucoma: A Review. Appl Sci. 2020;10(15). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Filipe H, Henriques J, Reis P, Silva P, Quadrado M, Serro A. Contact lenses as drug controlled release systems: a narrative review. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 2016;75(3):241-7. [Google Scholar]

- Soeken T, Ross A, Kohane D, Kuang L, Legault G, Caldwell M. Dexamethasone-Eluting Contact Lens for the Prevention of Postphotorefractive Keratectomy Scar in a New Zealand White Rabbit Model. Cornea. 2021;40(9):1175-80. [Google Scholar]

- Sahadan M, Tong W, Tan W, Leong C, MM, Chan M. Phomopsidione nanoparticles coated contact lenses reduce microbial keratitis causing pathogens. Exp Eye Res. 2018;178:10-4. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Rad M, Sabeti Z, Mohajeri S, BB. Fazly Bazzaz BS. Preparation, characterization, and evaluation of zinc oxide nanoparticles suspension as an antimicrobial media for daily use soft contact lenses. Curr Eye Res. 2020;45(8):931-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Ben-Shlomo G, Que L. Soft contact lens with embedded microtubes for sustained and self-adaptive drug delivery for glaucoma treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(41):45789-95. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R, Yang H. Hydrogel-based ocular drug delivery systems: emerging fabrication strategies, applications, and bench-to-bedside manufacturing considerations. J Control Release. 2019;306:29-39. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Irimia T, Dinu-Pîrvu C, Ghica M, Lupuleasa D, Muntean D, Udeanu D. Chitosan-Based In Situ Gels for Ocular Delivery of Therapeutics: A State-of-the-Art Review. Mar Drugs. 2009;16(10). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Lin S, Ge C, Wang D, Xie Q, Wu B, Wang J. Overcoming the Anatomical and Physiological Barriers in Topical Eye Surface Medication Using a Peptide-Decorated Polymeric Micelle. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(43):39603-12. [Google Scholar]

- Fang G, Wang Q, Yang X, Qian Y, Zhang G, Tang B. γ-Cyclodextrin-based polypseudorotaxane hydrogels for ophthalmic delivery of flurbiprofen to treat anterior uveitis. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;277. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Gao H, Chen M, Liu Y, Zhang D, Shen J, Ni N. Injectable Anti-Inflammatory Supramolecular Nanofiber Hydrogel to Promote Anti-VEGF Therapy in Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatment. Adv Mater. 2022;35(2). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Lee K, Goudie M, Tebon P, Sun W, Luo Z, Lee J. Non-transdermal microneedles for advanced drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;40(9):1175-80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Zhou X, Kim H, Qu M, Jiang X, Lee K. Gelatin Methacryloyl Microneedle Patches for Minimally Invasive Extraction of Skin Interstitial Fluid. Small. 2020;16(16). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Jiang J, Moore J, Edelhauser H, Prausnitz M. Intrascleral drug delivery to the eye using hollow microneedles. Pharm Res. 2009;26(2):395-403. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Zheng M, Wiraja C, Chew S, Mishra A, Mayandi V. Ocular Delivery of Predatory Bacteria with Cryomicroneedles Against Eye Infection. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2021;8(21). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Lee K, Park S, Jo DH, Cho CS, Jang HY, Yi J. Self-Plugging Microneedle (SPM) for Intravitreal Drug Delivery. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022;11(12). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Li N, Zhao L, Wei Y, Ea V, Nian H, Wei R. Recent advances of exosomes in immune-mediated eye diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Cheng S, Punzo C. Update on viral gene therapy clinical trials for retinal diseases. Hum Gene Ther. 2022;33(17-18):865-78. [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Shu X, Fan Y, Fan T, HZ. Recent advances in nanomaterial-enabled acoustic devices for audible sound generation and detection. Nanoscale. 2019;11(13):5839-60. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Xie Z, Chen S, Duo Y, Zhu Y, Fan T, Zou Q. Biocompatible Two-Dimensional Titanium Nanosheets for Multimodal Imaging-Guided Cancer Theranostics. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(25):22129-40. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Behnke R, Liang Y, You S, Tay D, Zhang S, So K. Nano neuro knitting: peptide nanofiber scaffold for brain repair and axon regeneration with functional return of vision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(13):5054-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Behnke R, Jonas J. Redefining tissue engineering for nanomedicine in ophthalmology. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;89(2):108-14. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Boo C, Ryu WH, Taylor A, Elimelech M. Development of Omniphobic Desalination Membranes Using a Charged Electrospun Nanofiber Scaffold. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(17):11154-61. [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg D, Shi J, Jain S, Chang J, Ripps H, Brady S. Impediments to eye transplantation: ocular viability following optic-nerve transection or enucleation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(9):1134-40. [Google Scholar]

- Kalishwaralal K, Barathmanikanth S, Pandian S, Deepak V, Gurunathan S. Silver nano - a trove for retinal therapies. J Control Release. 2010;145(2):76-90. [Google Scholar]

How to Cite This Article

Vancouver

Dubey S. Ocular drug delivery systems and nanotechnology [Internet]. IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 25];10(4):179-187. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.034

APA

Dubey, S. (2024). Ocular drug delivery systems and nanotechnology. IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty, 10(4), 179-187. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.034

MLA

Dubey, Shivam. "Ocular drug delivery systems and nanotechnology." IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty, vol. 10, no. 4, 2024, pp. 179-187. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.034

Chicago

Dubey, S.. "Ocular drug delivery systems and nanotechnology." IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty 10, no. 4 (2024): 179-187. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.034